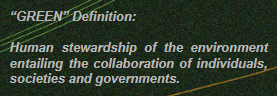

In response to the ‘GREEN FOR WHOM?’ prompt, my group (Haram Joung, Sanjana Rajesh, and myself) picked Lacoste’s ‘Save Our Species’ campaign to investigate, in which the iconic embroidered crocodile logo was replaced by embroidery of 10 endangered species.

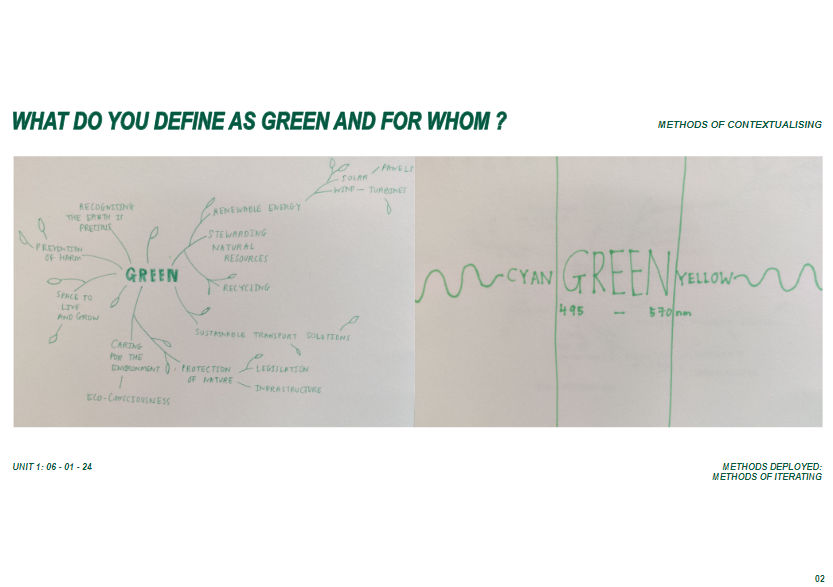

We started our investigations by considering the word, ‘green’, and iterated through ways of displaying its meaning – these were my initial ideas:

We compiled our ideas into one group definition:

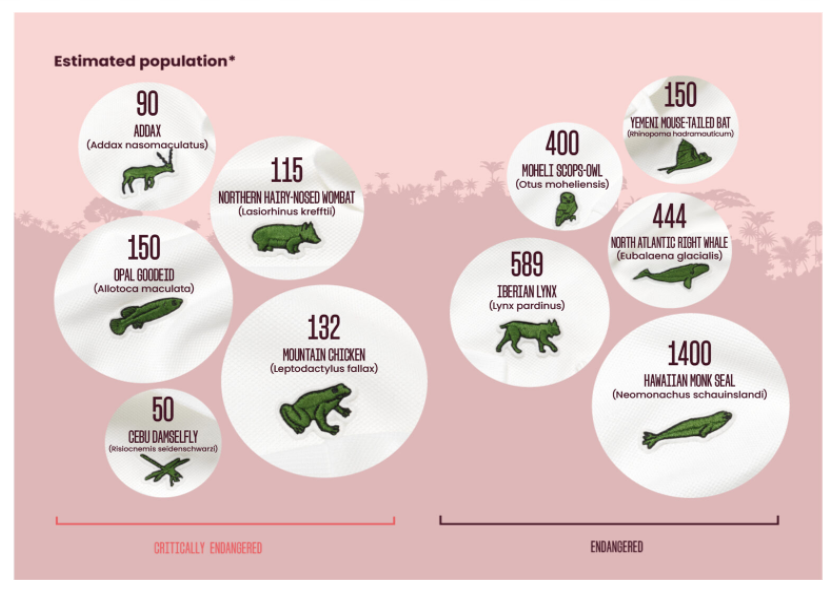

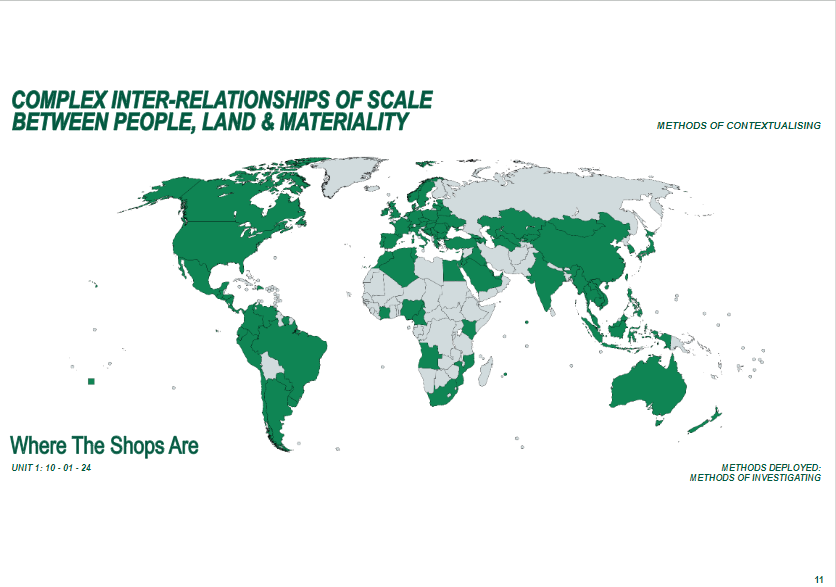

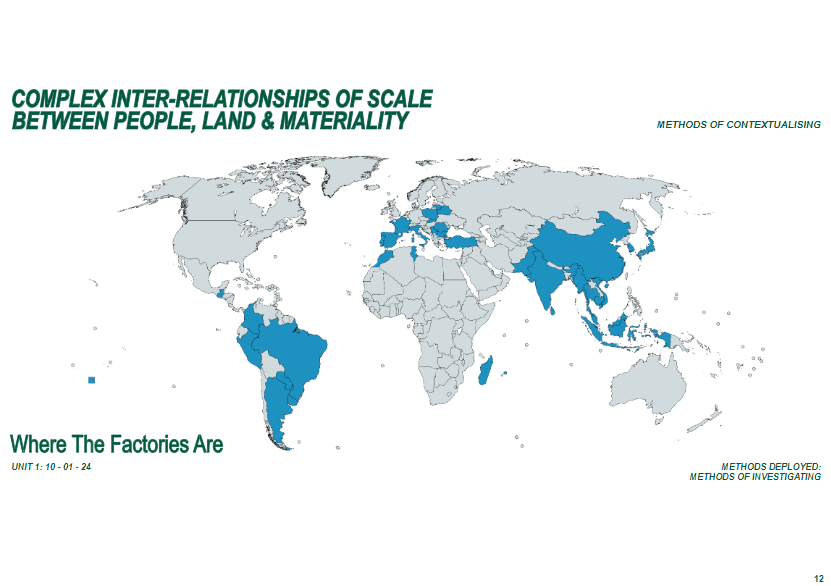

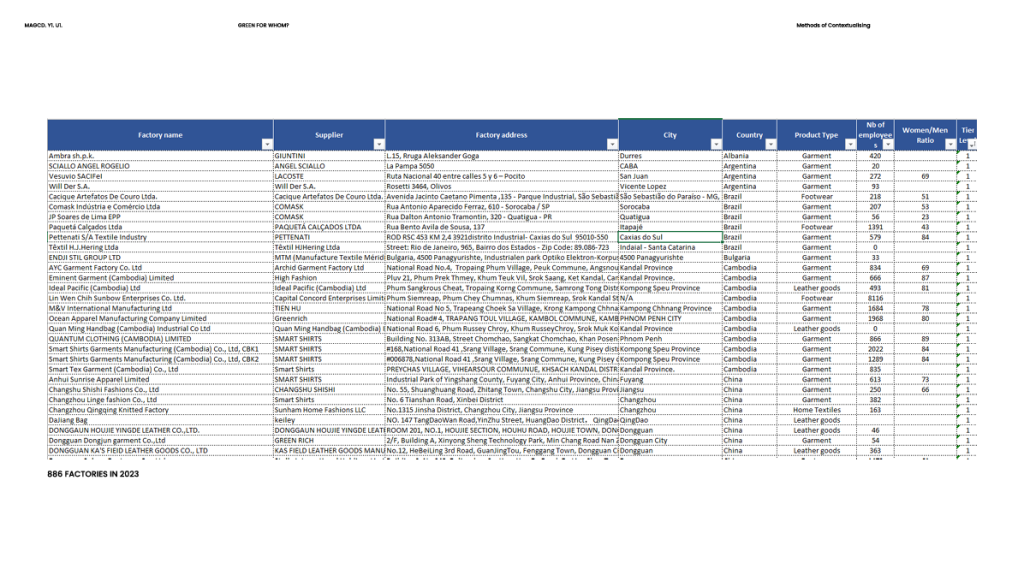

We split the factors of ‘people’, ‘lands’ and ‘materiality’ between us to investigate. I investigated ‘lands’. I looked up the locations of all the Lacoste stores (from their website), the locations of all their factories in the world in 2023 (which they published in a spreadsheet: https://corporate.lacoste.com/app/uploads/2023/03/Lacoste-Factories-List-to-publish-Jan-2023-avec-Tier-Level-et-City.xlsx), and the locations of each of the species in the campaign (which I looked up individually).

I plotted these three geographies in visual comparison on a world map, with France (the HQ of Lacoste) in the centre:

I thought it was interesting to compare the geographies of the animals being ‘saved’, the people buying the garments, and the people making the garments.

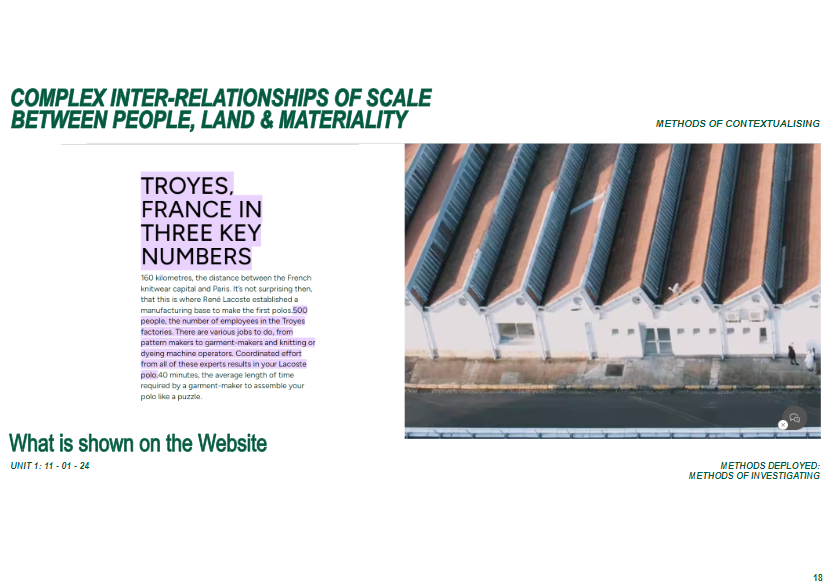

Interestingly, when investigating further into how Lacoste portrays the last category, the only factory depicted on their website is one in France, beneath clean and quick and catchy videos of sewing machines sewing crocodile logos.

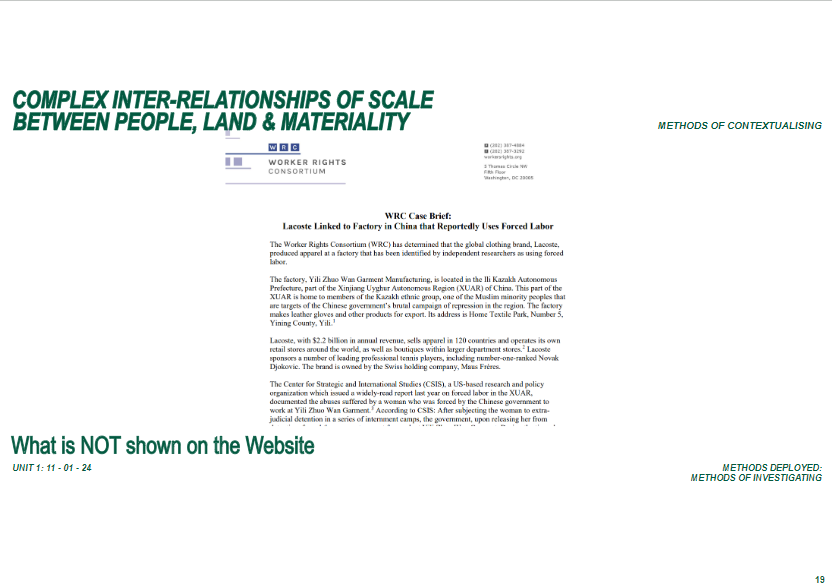

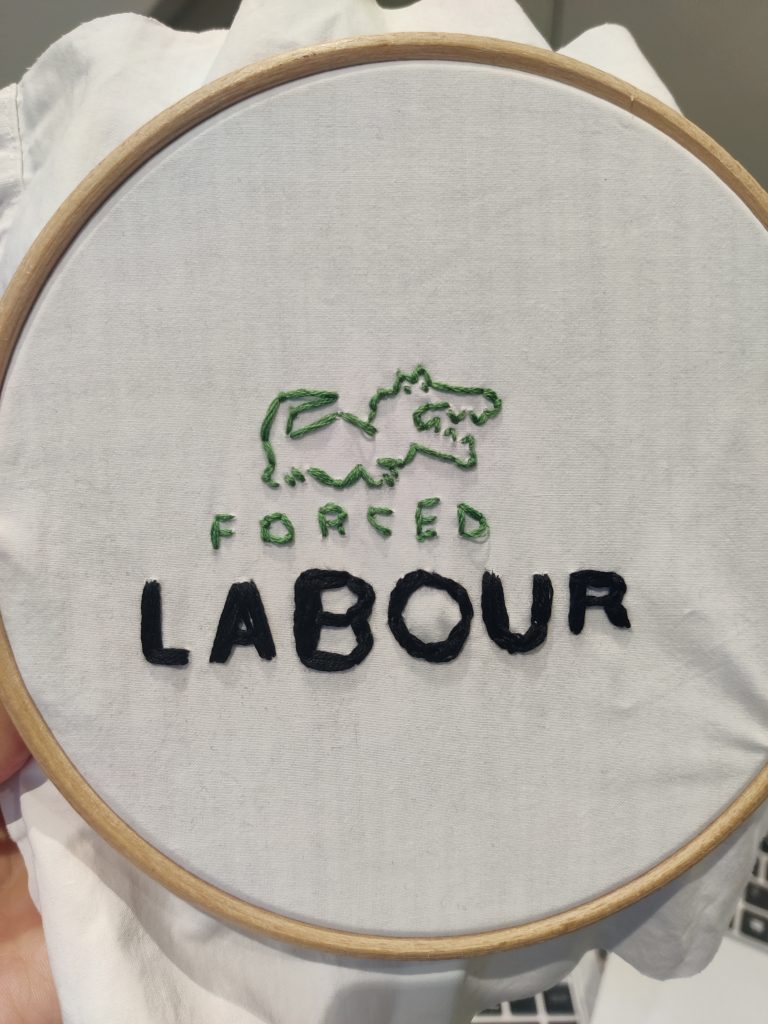

There are no images of their other factories all around the world. 28 out of their 886 factories are in France. 166 out of their 886 factories are in China. There was a 2020 report implicating Lacoste in the use of forced labour to make its apparel in China. This was the same time the campaign was running.

The graphic design decision to only show a French factory is interesting. Why the lack of transparency about their other factories? Is it OK to throw money towards animal conservation whilst exploiting people? Do they actually care about anything as much as their brand perception?

Our group decided to focus on areas of ‘leakage’ in the Lacoste fashion narrative: things which the public might not notice or pick up on, like how the campaign actually had an impact (if it did) on conservation efforts, who are the people making the clothes, and what the environmental impact of generating these garments is.

FINAL PRESENTATION

Our explorations of this topic lead us to question what actually constitutes a ‘green’ campaign.

Each of us focused on a particular area of ‘leakage’ in the Lacoste campaign: I focused on the factories around the world, interrogating the spreadsheet data that they published and also experimenting graphically with how to convey what we can glean from that data about the production process.

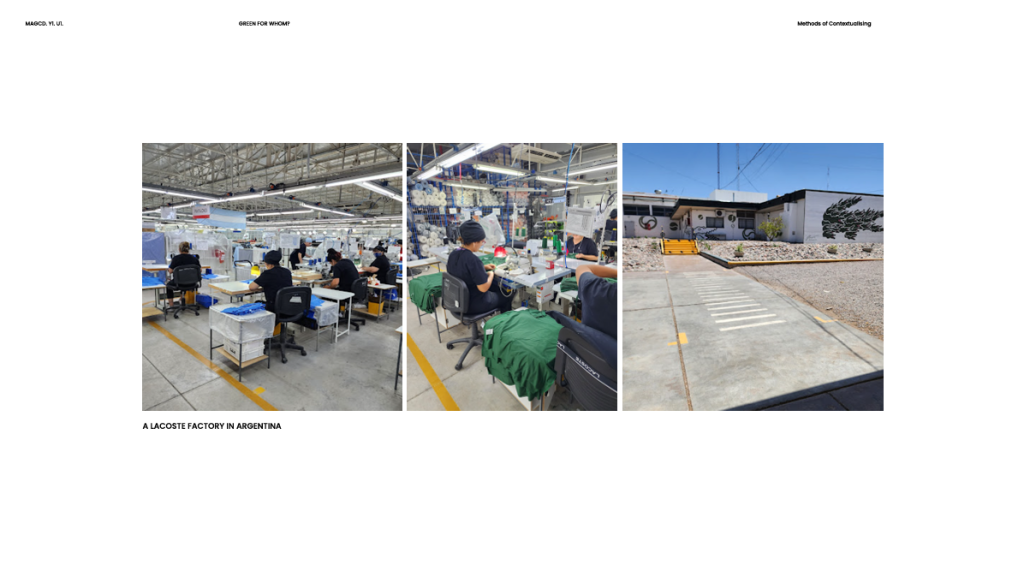

Many of the factories appear very ‘above board’. They are available on GoogleMaps and the public can upload images, e.g. this factory in Argentina:

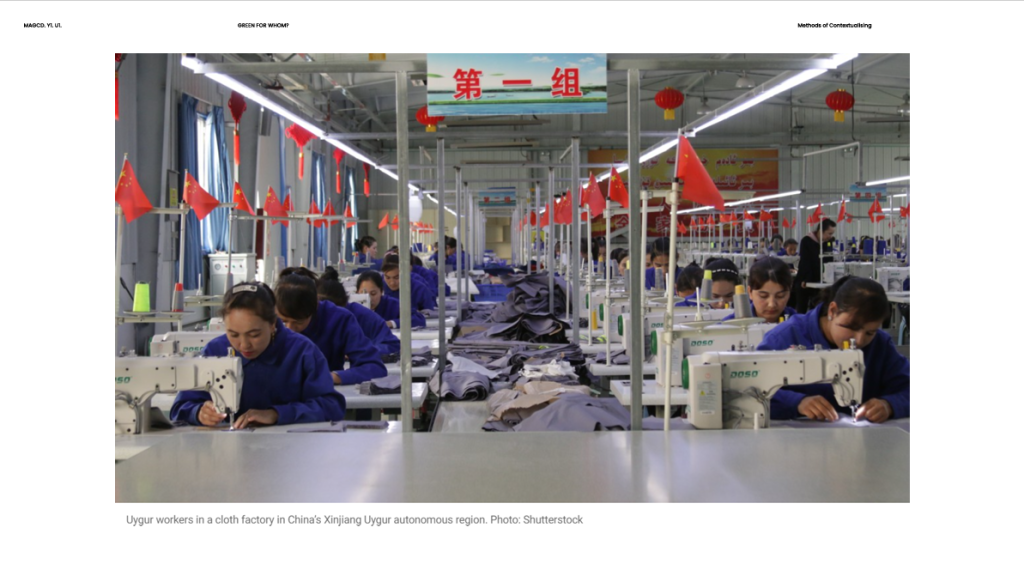

However, there is a mystery to many of the factories in China. Though the spreadsheet includes their addresses, nothing appears in an internet search. Their addresses are not available on GoogleMaps, and there is nothing available. I found an image in the Taipei Times of a likely re-education camp for Uygur people (which are the people group the report highlights as being in forced labour for Lacoste).

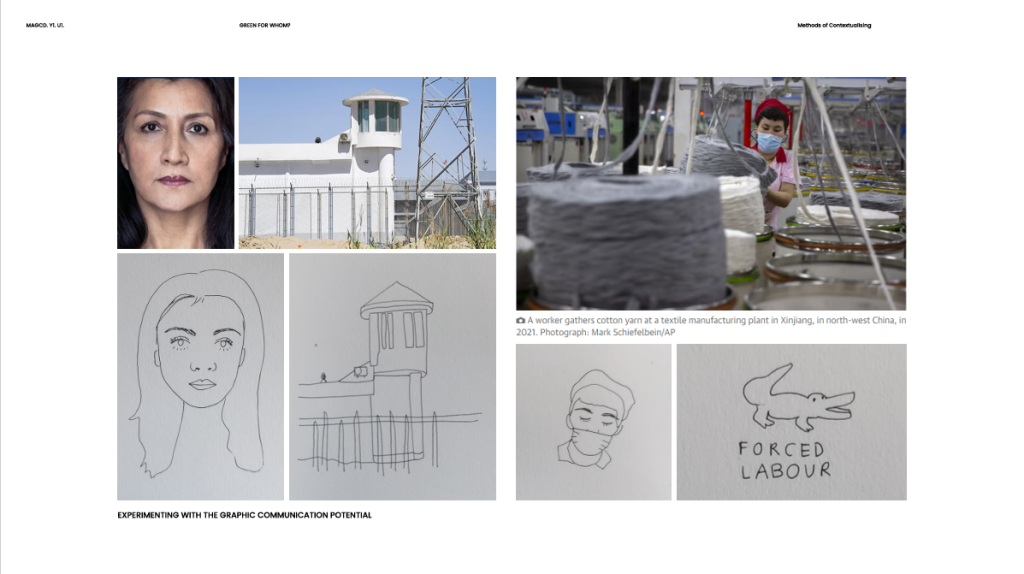

A watchtower from what is believed to be a ‘re-education’ camp for Uygurs linked to the Lacoste supply chain (https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2020/03/05/2003732101)

There were no pictures of the workers from the factory condemned in the report – most images of Uygur workers in factories I could find were in newspaper articles.

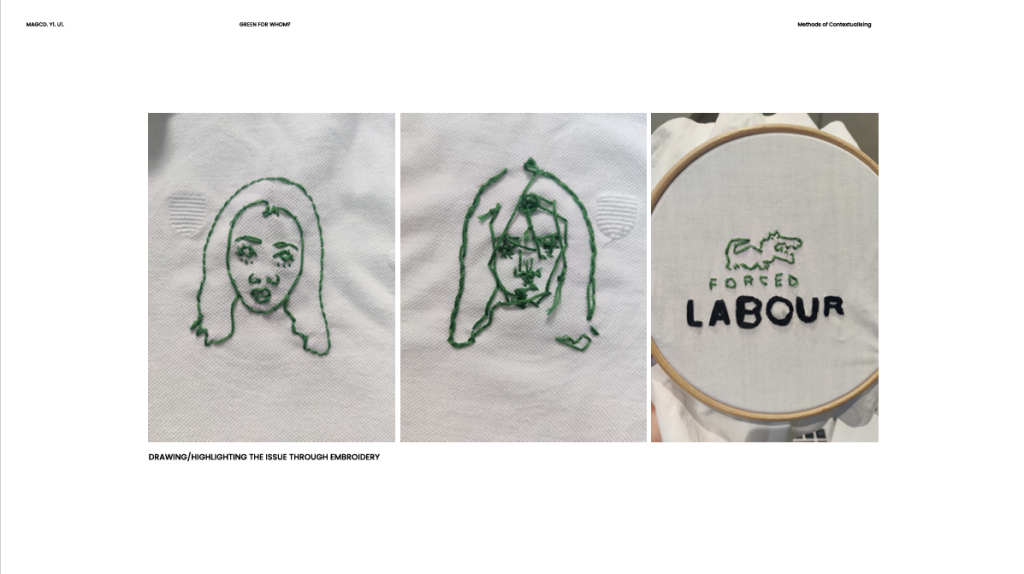

I loosely illustrated the images that we could find about the Uygur forced labour workers and played with translating them into embroidery (mimicking Lacoste’s logo campaign but satirising what that campaign stands for).

Though we started with the question of what constitutes a ‘green’ advertising campaign, our explorations also lead to questioning the role of a graphic communication designer within this context. It seems up to the designer to decide which ‘leakages’ remain hidden and which are conveyed to the public eye.