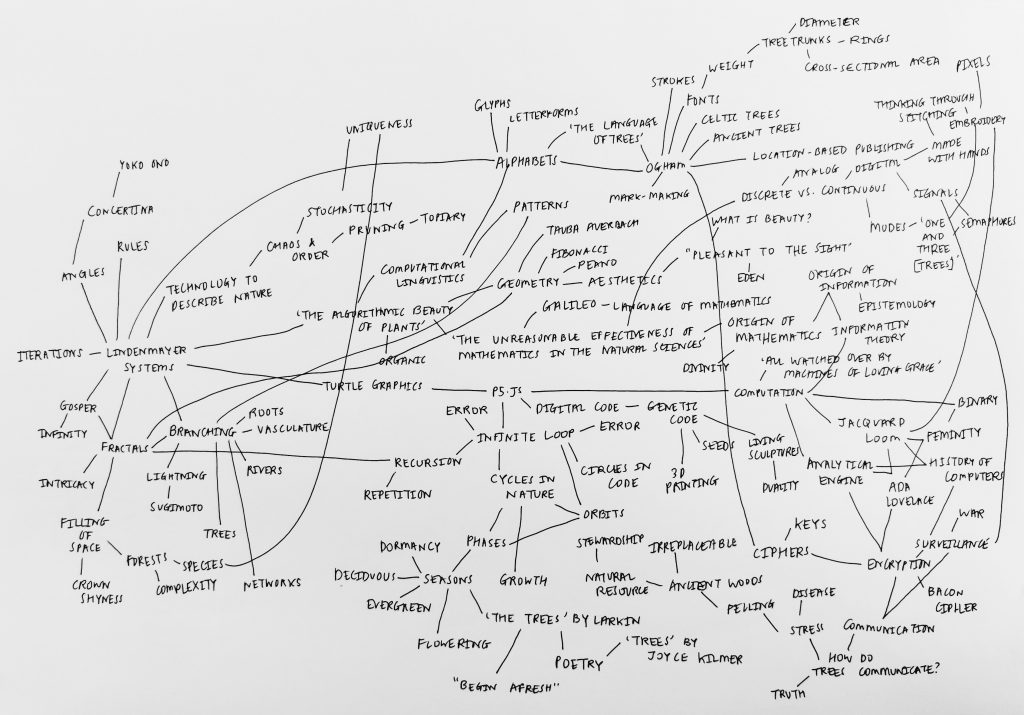

The small magazine, Pleasant Place, is about the art of gardening, and its sixth issue is about topiary. As with my own work, its subject matter is an area of intersection between mankind and nature, but its allure about the sculpting of existing plants, rather than an emulation of their existing structures. I am looking at growth and branching; the reference is looking at pruning and shaping.

Its main challenge to my work in terms of position reconsideration is in the presentation and conveyance of my project: what thus far has comprised loose visual outputs in JavaScript-ed, embroidered, hand-drawn, gestured forms could be bound together in a way which is effective as a physical publication. It could be distributed and digested in a way that is different, and it could be taken to places it wouldn’t otherwise go. Pleasant Place’s green botanical theme also encourages the germination of ideas in my project about how an ancient woodland publication might be presented. It would be good to visit an ancient woodland to investigate the colour palette and atmosphere, and to explore how this might be recorded.

Another challenge to my project is in regard to the strength of my contextualisation: the last page of the magazine declares it “caters both to those who grow gardens as well as those who imagine gardens” – who is my project catering to? Its audience is still somewhat undefined but could be anyone. Though Ogham is cryptic, the key renders it accessible to anyone, and it could be used educationally as a key to understanding, as well as to pique curiosity. That might be curiosity about branches, about natural structures, about growth, about trees, about ancient alphabets and ancient trees, about stewardship, about other thoughts that could branch from these. Ancient woodlands need preservation, and a modern use of Ogham might be useful in highlighting and conveying this. In this sense the reference is in tension because its appeal is to those already interested in gardens, but my enquiry, though it may be quite inaccessible without a key (though some minds might work it out), could appeal more broadly.

A head gardener quoted in the reference states that “topiaries are horticultural things, they’re historical things, but as much as anything, I feel a social history here”. Similarly, ancient woodlands and the Celtic tree alphabet “are horticultural things, they’re historical things, but as much as anything, I feel a social history here”. There is something very soothing and grounding about being in woodland, and more so being among trees that have been present as many human generations have gone by. I, myself, sprig from an Irish familial tree in part, so my own genetic roots position me in affiliation with Ogham’s cultural history as an alphabet for writing Irish. But Ogham inscriptions were also found in other places in the British Isles, so it is not unnatural to apply Ogham to trees in England. The reference, through its historical consideration, provokes thought about the historical roots of my project, which it would be good to dig deeper to find out more about.

There is an interesting parallel between topiary, where “gardeners train branches along guide wires of a predetermined form”, and the shaping of ‘trees’ into a system of set branching letters in Ogham. The ‘wildness’ of plants in topiary is tamed, sometimes into “preordained” geometric shapes, whereas Lindenmayer systems and Ogham letters are predetermined from the get-go; there is not a wildness that is tamed. The reference and my project are looking at living branching forms and transforming them into simpler geometric shapes: the former shaping the actual plants themselves, the latter mimicking the architecture of branches in a form of mark-making. The reference’s topic is an art form involving the subduing of nature and the curbing of its shapes according to a gardener’s whims, but the simplification in my project budded from an interest in learning something about the shapes of plants in their natural form. It respects the wildness of the shapes of “a tree in all its luxuriancy and diffusion of boughs and branches”, though it cannot fully capture it.

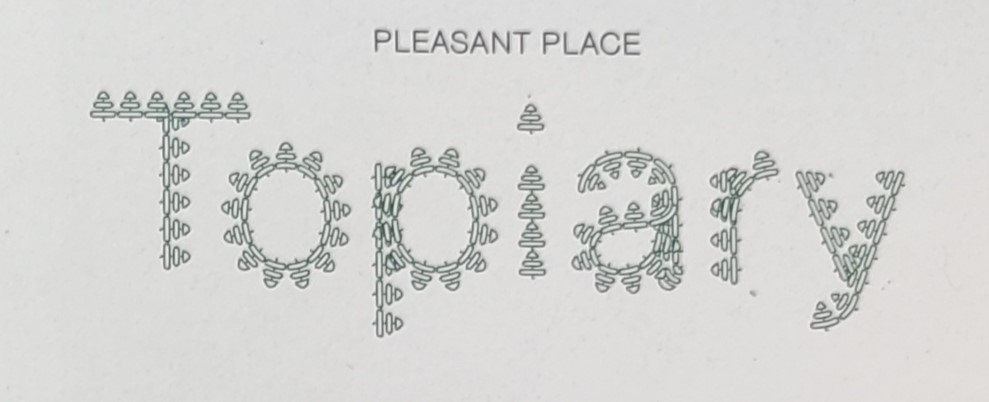

A weakness that struck me about the reference is its header font: each of the letters comprises the same little topiary illustration repeated around the shape of the letters, like a little line-drawn block print.

Sometimes there are overlaps, which feel a bit cluttered. Though it resembles topiary on repeat, it does not really convey much of the character of topiary, apart from kitsch-y-ness. This is unlike Ogham, with which branches can be written in branches. Perhaps there are ways that Ogham could be developed into different fonts which further reflect the characteristics of different trees. As the thickness and texture of trunks can be changeable, and the branching ‘style’, there is potential to play with the font weight and style of Ogham.

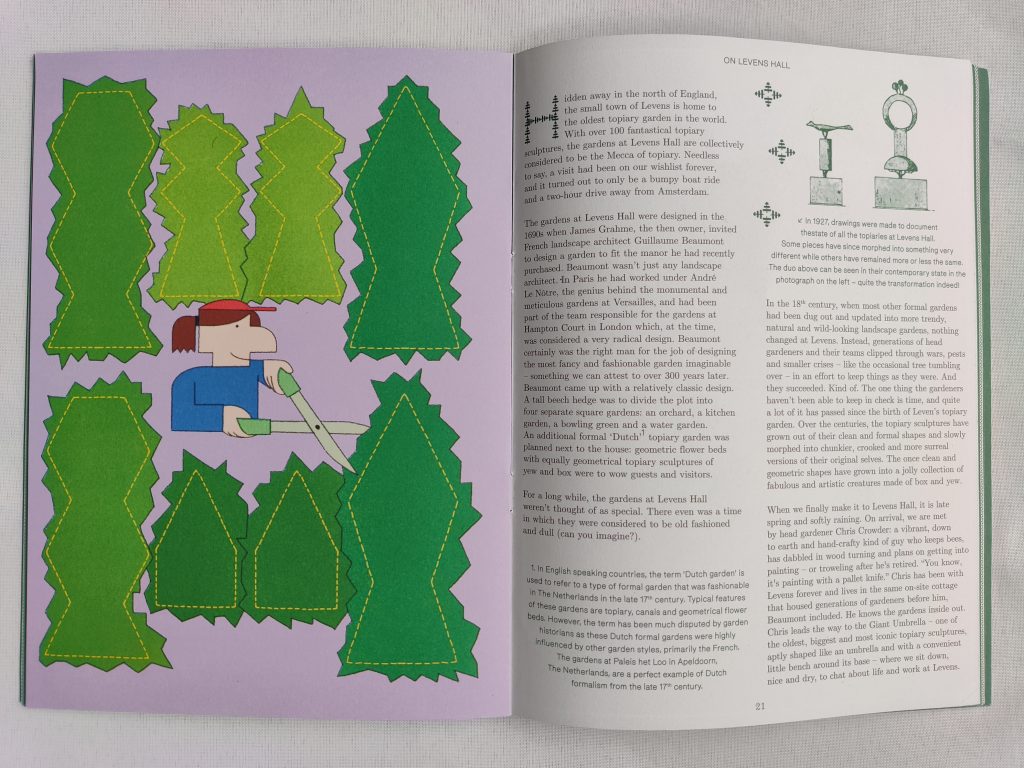

Something interesting about the reference is that the centrefold of the publication has topiary illustrations one can cut out and assemble. It is clever how the reader can go through the motion of cutting out paper topiary, mirroring the way actual topiary is often sculpted, using what look like giant scissors. Is there a way of making a reader of a publication about Ogham somehow ‘grow’ a branching structure or interact in a branch-mark-making way?

The idea of taming of organic ‘chaos’ through the art of topiary brings back to mind what was unreal about my early Lindenmayer graphics: I did not interweave any stochasticity. There was not randomness. But in topiary, orderliness is imposed upon the wildness. This is matched in Ogham’s orderliness. Each letter represents a real, wild tree, but its human-written form comprises a simply stroke (branch) pattern. This is useful for ease of comprehension and for usability. Yet different tree species do manifest different branching patterns. In this way the reference has helped me reflect upon complexity (geometric and aesthetic) and how useful simplification can be as a way of making sense of it.

The reference (in reference to Japanese topiary) states “[t]he art reaches its finest form when the artifice of the human hand is all but invisible”, but in writing with Ogham, the “human hand” is the author the work, and in preservation of ancient woodland, human hands must go hand-in-hand (metaphorically) to protect and look after these resources. But in topiary and in learning about and looking after ancient trees, perhaps the human is more like an art handler; the difference is how the living sculpture of a tree or shrub is handled. A tree or shrub in the real world is 3D-printed from genetic code, with environmental inputs shaping it along the way, and human hands have the freewill to intervene dramatically.

An idea from Pleasant Place which challenges me is a line which reads that topiary reveals an aspect of human nature, “the unrelenting desire to control and sculpt our surroundings. To force the unruly natural world into submission, as if we were tiny gods on earth.” It implies that there is something wrong with ‘taming’ nature. Though I am looking at the protection and preservation of irreplaceable ancient woodlands, the motivation for that is one of stewardship. I reject the notion that it is not our place to interfere at all with nature as though we were “tiny gods”, but rather hold that it is our privileged position as humans to be able to use resources from but also to look after the natural world. The reference hints at an anti-humancentric view when it talks about “the belief that nature needs mankind”. While it is not true that to steward the earth necessarily entails the shaping of shrubbery, if one were to consider a theocentric position, where Man’s role in nature is “to tend and keep it” (Genesis 2:15, NKJV), maybe nature does need mankind. Perhaps the ‘tending’ of nature can render it more beautiful and beneficial to societies. To “tend and keep” ancient woodlands is not to exploit them, but to preserve them and the wildlife therein, without precluding the possibility of using natural resources sustainably for humans to survive and thrive.

The art of “[t]rimming, clipping and pruning” which the Pleasant Place celebrates, though in tension with my project in some ways, has also been helpful as part of the process of my line of enquiry, in which ideas had to be selectively pruned back and trimmed as they budded and grew in different potential directions.

References

- (2024) ‘Topiary’, Pleasant Place, (October).

- NKJV Bible. Available at: https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Genesis%202&version=NKJV